The average life expectancy of workers in Iceland has shortened in recent years, while the average life expectancy of university graduates has increased. This is a change from most of the last century when people’s life expectancy generally increased. The explanation may lie in the changing composition of the workforce when it comes to its origin. The average life expectancy of all men and women in Iceland, regardless of education, decreased between 2022 and 2023.

Stefán Ólafsson, professor emeritus and expert at Efling Union, points out these changes and relies on new figures on average life expectancy after education that Statistics Iceland recently published. Although the classification is, as mentioned above, based on education, education is an approach to classifying people into occupations.

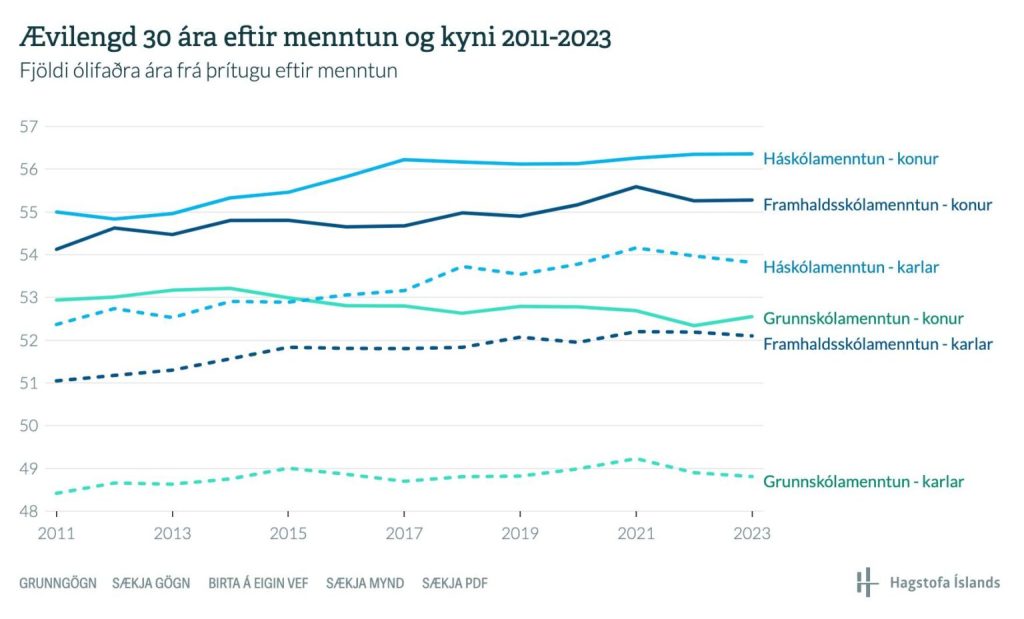

The figures show that university-educated men live about five years longer than men with a primary school education, but the latter group is most often in blue-collar jobs. The average life expectancy of male workers last year was 78.8 years. If the average lifespan of male workers is compared with the average lifespan of university-educated women, it turns out that the latter live about eight years longer on average.

The average life expectancy of primary school-educated women, female workers, rose between 2022 and 2023 but had fallen sharply between the years 2021 and 2022 before. The average life expectancy of female workers last year was slightly lower than in 2021, 82.6 years. The average life expectancy is 3.8 years shorter than that of women with a university education and 2.7 years shorter than that of women with a secondary school education. The average life expectancy of university-educated men is 1.2 years longer than that of working-class women.

When one looks at the development of the last decade, one can see that the average life expectancy of female workers has shortened by 0.6 years since 2014. The average life expectancy of male workers has remained the same at the same time. However, the average life expectancy of all other groups has increased, most for university-educated women, by 1.1 years. Last year, the average life expectancy of university-educated men was 0.9 years higher than in 2014, and the average life expectancy of both men and women with secondary school education was 0.5 years longer than a decade ago.

Stefán says that in the last century, people’s life expectancy in general was growing, but now the life expectancy of workers has been shortening in recent years. “There is a big change for the worse,” Stefáns writes. He believes that the explanation is not least to be found in the changed composition of the workforce in Iceland. The increase in the number of workers of foreign origin who were brought up in poorer living conditions and poorer livelihoods than native Icelanders affects the decreasing average life expectancy, and that effect will presumably be felt to a greater extent in the coming years.