Stefán Ólafsson writes:

Although wages are generally quite high in Iceland, the income of wage earners’ households is worse than in general in the other Nordic countries. This is explained mainly by higher prices in Iceland, a poorer welfare system, and extremely high housing costs, mainly due to the higher interest rates of housing loans and high rent. In reality, the poor housing situation has damaged the living conditions of Icelandic households more than what happens in the other Nordic countries – and still does. The economic management of the government and the Central Bank is worse in Iceland by this amount.

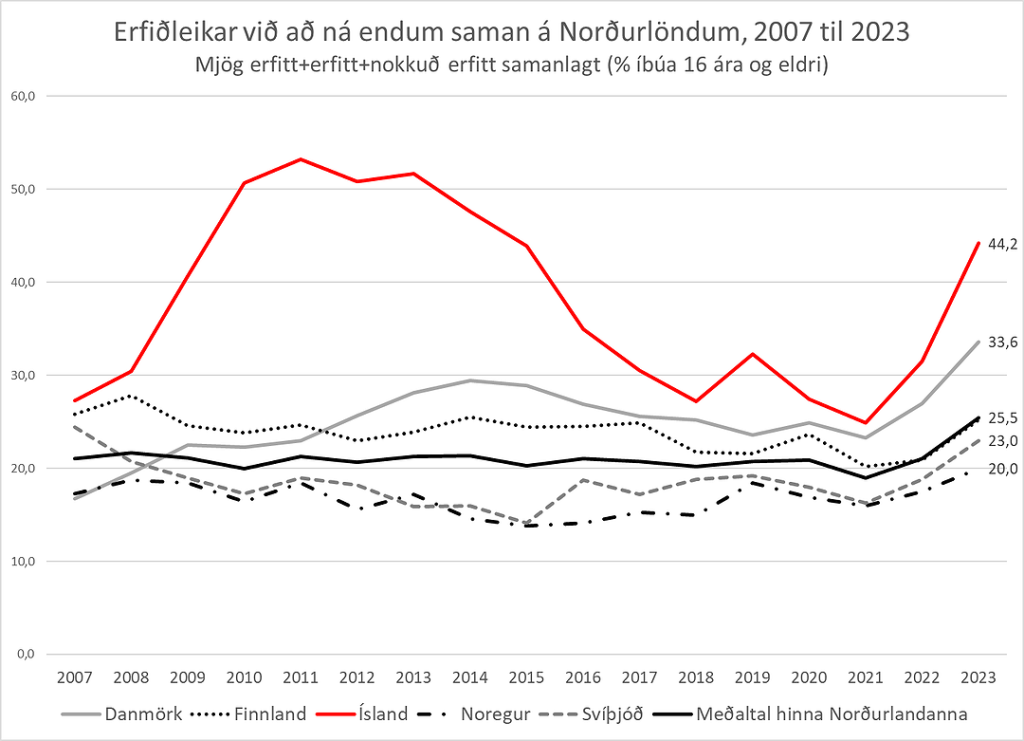

This is shown by figures on the difficulties of households in making ends meet in everyday life (see Figure 1). The comparative statistics cover the period from 2007 to 2023. In all years, the percentage of households that say they have difficulty making ends meet is the highest in Iceland. The difference is by far the largest, to Iceland’s disadvantage, when the economic downturn has hardened, such as following the financial crisis 2008 and after inflation and key interest rates increased sharply in 2022 and 2023.

This suggests that economic hardships are weighing more heavily on households in Iceland than in the other Nordic countries. In that respect, economic management in Iceland is more unfair towards households. Burdens due to difficulties are to a greater extent transferred onto the shoulders of workers in Iceland.

The picture clearly shows how much household conditions have worsened in the years following the Covid crisis.

Image: Eurostat and Varða surveys

After the financial collapse of 2008, the percentage of households struggling to make ends meet in Iceland went from around 27% in 2007 to around 53% in 2011, while there was little change in difficulties in the other Nordic countries. After 2011, difficulties in earnings increased somewhat in Denmark until 2014, but nothing like the increase in Iceland.

After inflation increased from the second half of 2021 until 2023, running a household became heavier in Iceland, much more than in the other Nordic countries, as the figure shows.

Here, the percentage of households in difficulty went from almost 24% in 2021 to around 44% in 2023. The increase was close to 20 percentage points. The largest increase was in Denmark of the other Nordic countries during the same period, or from 23.3% to 33.6%. The increase there was therefore about 10% points, or about half of what happened here.

Among the other Nordic countries, the average increase in income difficulties from 2021 to 2023 was about 6.6 percentage points compared to a 20 percentage point increase in Iceland. The situation thus worsened by far the most in Iceland, even though the course of the economy (economic growth) was much better here than in the comparison countries, both in 2022 and 2023. The high economic growth went mostly to increased company profits alongside a worse situation for workers.

The results have improved slightly in the spring of 2024, according to a new survey by Varða. Instead of over 44% of wage earners’ households struggling to make ends meet, the percentage dropped to almost 41%, following the fall in inflation. However, this is a small improvement.

It can then be expected that when the effects of the new collective agreement on the public market are fully realized (autumn 2024), the situation will improve even further. But how much hangs on the progress of lowering inflation and the interest rate – which has not been encouraging so far.

The situation in 2023 was dire from the workers’ point of view. In general, the lower income classes find it the most difficult to make ends meet, as they have less leverage when inflation and interest rate hikes hit.

European countries compared in 2023

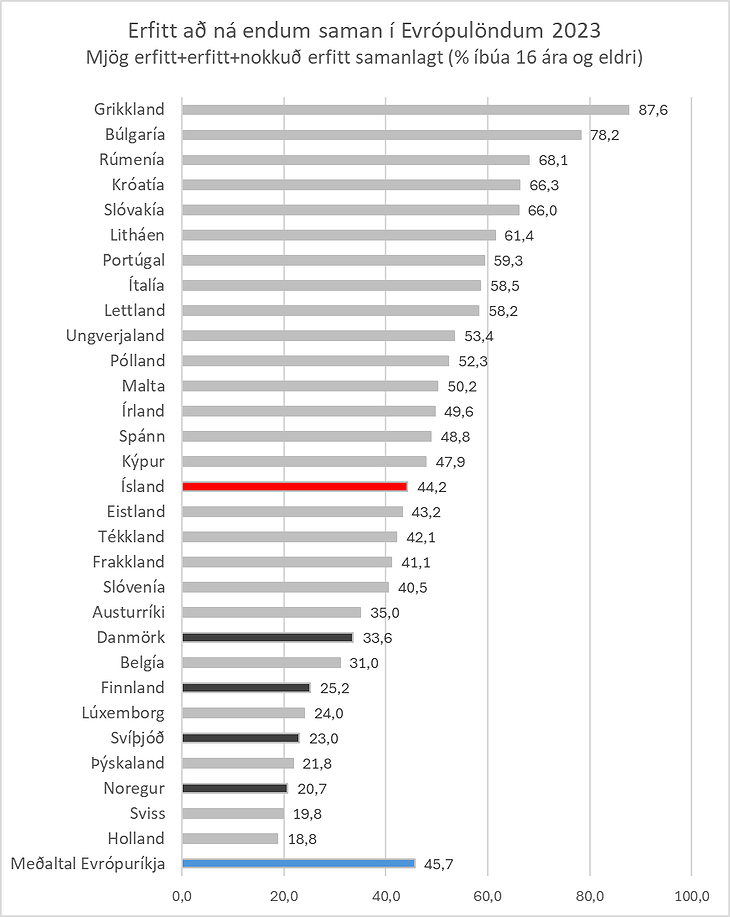

As Figure 1 shows, the situation in Iceland had worsened a lot from 2022 to 2023. But how did the situation in Iceland compare to most of the European countries last year? It can be seen in Figure 2.

Image: Eurostat and Värda surveys

In the year 2023, 14 European countries had less household economic difficulties than Iceland. In 2022, however, only about 8 countries had less difficulty making ends meet than was the case in Iceland.

Iceland was close to the average of all European countries last year, although the nation’s level of prosperity and natural resources should indicate a much better household performance.

Summary

When everything is put together, it appears that the position of wage earners is generally worse in Iceland than in the other Nordic countries. When the economic downturn hardens, the burdens of households also get heavier in Iceland than in the other Nordic countries.

Thus, a much higher percentage of households had difficulty making ends meet here than was the case in the neighboring countries in 2023, or about 44% of households in Iceland compared to 25.5% in the other Nordic countries on average. The lowest was about 20% in Norway.

The actions taken in the fight against inflation in Iceland have thus put a much heavier burden on the households of workers than in the other Nordic countries.

Stefán Ólafsson is a professor emeritus at the University of Iceland and works as an expert at Efling union.

The article was first published in Heimildin on September 15th, 2024.