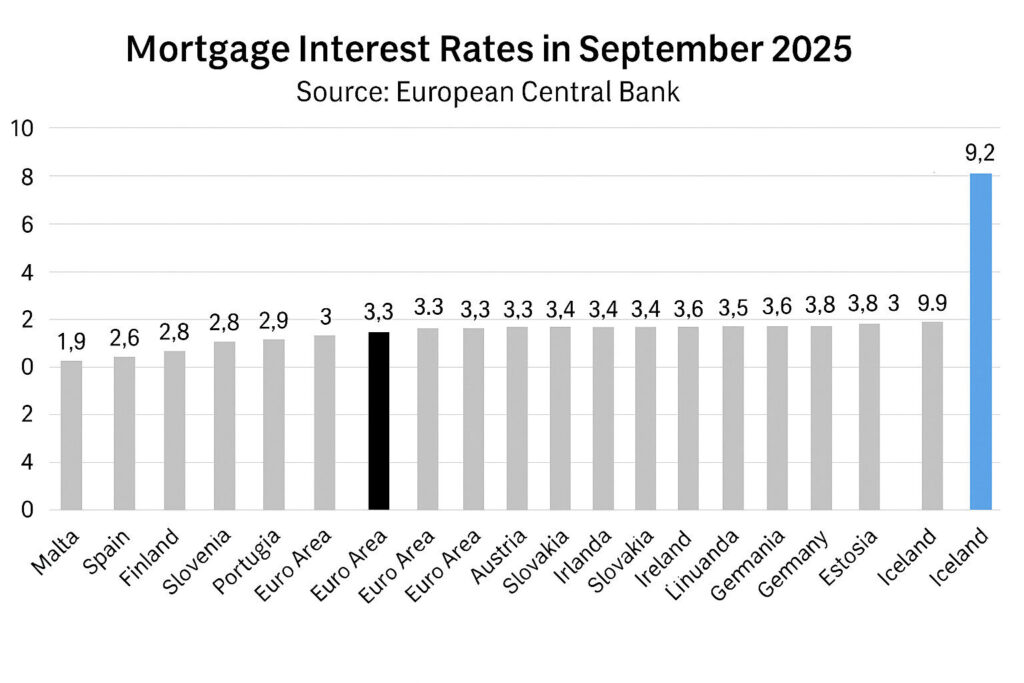

Iceland experiences abnormally high interest rates compared to neighbouring countries, and the cost of capital has become an excessive burden on both households and businesses. This is highlighted by Stefán Ólafsson, professor emeritus and specialist at the Efling trade union, in the article below. The main reason for these extremely high rates does not lie in the króna or indexation but in the enormous profits of the banks. Their profits are many times higher than in other sectors. They are driven primarily by interest income, which has risen sharply in recent years and is the key explanation for the high interest rate level.

Banks are acting like leeches on households and businesses

The banks operate with an unusually high equity ratio yet still deliver a 12 to 16 per cent return on equity, which is high in international comparison. Savings in operating costs have not been passed on to customers; instead, they have further increased the banks’ profits.

“Banks in effect impose super taxes on households and businesses in the form of interest on mortgages and corporate loans. Far beyond what is seen in neighbouring countries. They now appear set to raise rates and loan payments even further, following the recent interest rate ruling.

In truth, one might say that the banks lie like leeches on households and businesses and seem likely to drain even more. If that happens, the housing crisis will worsen and inflation will rise, other things being equal,” Stefán writes.

Stefán concludes that the banks can, and should, lower interest rates significantly by accepting more modest profits. This would create scope for lower rates on both household mortgages and business loans, easing the heavy burden that the current interest rate environment places on society. Without change, there is a risk that the housing crisis will deepen, inflation will increase, and confidence in the króna will erode even further.

Can the banks lower interest rates?

Iceland has long lived in a high-interest environment. Mortgage rates for households and loan rates for businesses have been much higher here than in neighbouring countries, as shown in the comparison in the appendix. This means that the cost of capital forms an excessively large share of expenses for both households and companies, which is a serious indictment of the Icelandic financial system.

But is it inevitable that things are this way?

In this article, I argue that the situation is abnormal and that it would be easy to improve it significantly if there were the political will to do so. The main responsibility lies with the banks, which price their services far too high. The enormous profits made by the banks, most of which come from interest income, are the key explanation for the high interest rate level, not the króna or indexation.

Excess profits in the banking sector

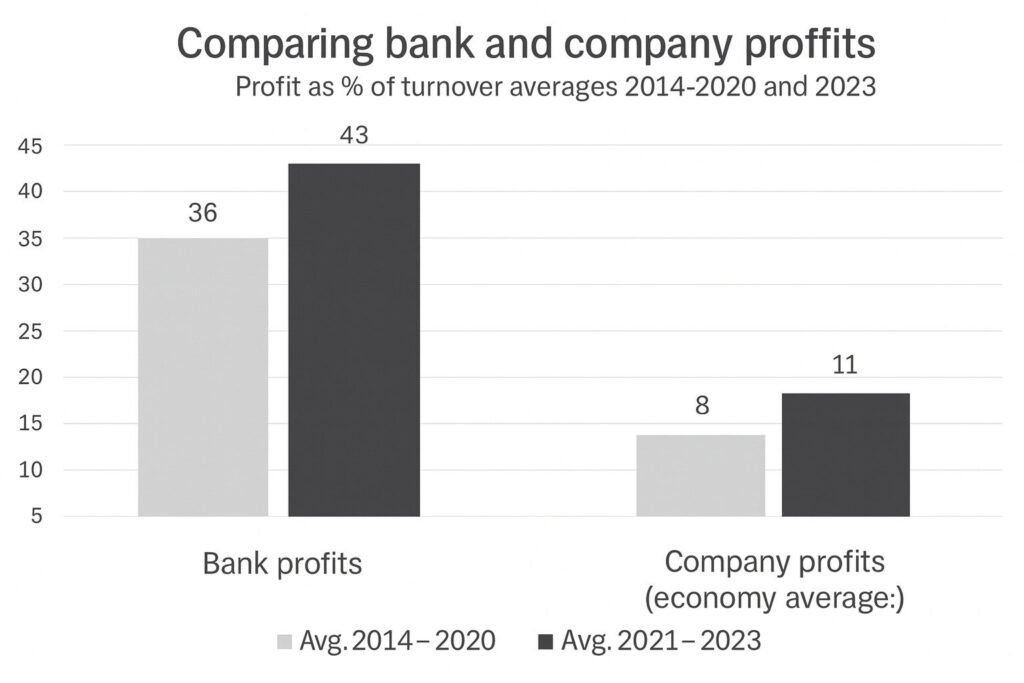

Let us begin by looking at the profits banks typically take for themselves. The accompanying chart shows profit as a share of turnover, that is, the operating income of the banks, compared with the average for other firms in the Icelandic economy. This is a common measure of the profitability of business activity.

As the chart shows, the banks’ profits were 36 per cent of turnover from 2014 to 2020, rising to 43 per cent when inflation picked up from 2021 to 2023. This was a substantial increase. Over the same period, the average company in Iceland showed an after-tax profit of about 8 per cent, rising to around 11 per cent in recent years.

Bank profits are therefore roughly four times higher than those of the firms that create the real value in the economy. This is an extraordinary difference. How did it come about?

Most of the banks’ income is interest income. This made up about 62 per cent of operating income from 2014 to 2020 and then increased to about 73 per cent from 2021 onwards. Rising inflation and higher policy rates magnified the long-standing boom of the Icelandic banks. The rest of the banks’ profits come mainly from service fees. The cost of capital that households and businesses must bear is what generates this excess profit.

For comparison, the profit share of the fishing industry is around 20 per cent in good years. Retail, including supermarkets, is at about 6 per cent and construction companies at around 10 per cent, against the banks’ 43 per cent. Banks are therefore operating in an entirely different world from the rest of society.

Banks, in effect, impose super taxes on households and businesses in the form of interest on mortgages and investment loans. Far beyond what is seen in neighbouring countries. They now appear set to raise rates and repayment burdens even further, following the recent court ruling on interest.

In truth, one might say that the banks lie like leeches on households and businesses and seem likely to drain even more. If that happens, the housing crisis will worsen and inflation will rise, other things being equal.

The banks’ weak defence

Many are shocked when they see the banks’ profit figures, which have grown sharply in recent years. This year looks likely to be a record year for the three major banks, possibly even with higher profits in krónur than the entire fishing industry, despite its much larger scale. When this is criticised, the banks’ main defence is usually that their return on equity is modest compared with banks in neighbouring countries. These claims are, however, highly misleading.

Icelandic banks are unusual in that they hold much more equity than is common in European banks, far above the minimum requirements under EEA and Icelandic rules. The higher the equity ratio is, the harder it is to achieve high returns on equity, even when profits are very large.

Yet despite this unusually high equity ratio, the banks’ return on equity is still very strong, between 12 and 16 per cent according to the nine-month results for 2025. Pension funds, for comparison, set themselves a minimum target of 3.5 per cent real return on assets, which is considered sufficient to cover future pension payments and their operating costs.

After the 2008 banking collapse, a very large amount of equity was injected into the banks to increase stability, which explains their high equity ratios today. We have, however, moved past the point where this is needed, as banking operations are now relatively secure. It is therefore appropriate for the state and the Central Bank to facilitate a reduction in equity ratios. This would allow the banks to achieve an acceptable return without seeking excess profits.

Although the Central Bank’s abnormally high policy rates do play a role in today’s high interest rate environment, this does not justify the additional burden the banks place on top of the policy rate or other benchmarks.

Whichever way one looks at it, it is clear that Icelandic banks are pricing their services unreasonably high. Interest rates for both households and businesses are too high, margins and mark-ups are too high, and service fees likewise. The banks’ demanded return on equity is also too high.

Over the past decade, the banks have substantially increased efficiency, with fewer branches and staff and more self-service through online banking. There is no sign that this reduction in operating costs has been passed on to customers through lower loan rates or lower service fees. On the contrary, it appears to have gone almost entirely into pushing bank profits even higher.

Banks can and should lower interest rates

The banks are taking too large a share of society’s value creation and too large a share of household disposable income, far more than is seen in neighbouring countries.

Their profits are completely out of proportion to the profits of other Icelandic companies. The banks cannot credibly blame high funding costs or challenging operating conditions. Even in Iceland’s high-interest environment, they achieve these excess profits.

If the banks accepted reducing their profit share by half, from over 40 per cent to about 20 per cent, they could deliver substantial interest rate reductions for both businesses and households. Even then, they would have a profit share similar to or higher than the fishing industry, which has built up substantial equity in recent years. The banks would hardly suffer by operating at such a level of profitability.

If the banks lower interest rates, the pension funds will follow. As things stand, pension funds cannot offer significantly better loan terms than the banks because most borrowers would then shift their mortgages to the funds, making housing loans too large a share of their portfolios for proper risk diversification. The banks, therefore, need to take the lead on lowering rates.

If the Icelandic financial system cannot offer interest rates comparable to those in neighbouring countries, demands for higher wages will inevitably grow. The trade union movement will then have to respond. Another likely outcome is that a majority of the public and business leaders will increasingly turn away from the króna and demand entry into the EU and adoption of the euro, in the hope of more reasonable interest rates.

The simpler and quicker solution, however, would be for the banks to align themselves with the reality of the Icelandic economy and society and significantly reduce interest rates and service fees by giving up at least half of their excess profits.

A great deal is at stake. The current situation is intolerable for both households and businesses.

Stefán Ólafsson is a professor emeritus at the University of Iceland and a specialist at Efling Union.

The article was first published on Heimildin’s website on 15 November 2025.